by FPDieulois :: 2025-10-30

The 13th Floor (1999), directed by Josef Rusnak, is an underrated gem in my 50 favorite films, a cerebral Sci-Fi thriller that predates The Matrix (1999)

by months and explores layered virtual worlds with chilling precision.

While Ridley Scott’s visual flair in films like Blade Runner captivated me, his later narrative stumbles in Alien:

Covenant (2017) highlighted the risks of style without depth;

Rusnak, however, delivers a taut, philosophical ride, bolstered by Craig Bierko’s haunted intensity,

Gretchen Mol’s enigmatic allure, and David S. Goyer’s intricate script.

Adapted from Daniel F. Galouye’s 1964 novel Simulacron-3, it probes the fragility of reality, leaving us to question if we’ve truly escaped the simulation.

The story unfolds in 1990s Los Angeles, where tech mogul Hannon Fuller (Armin Mueller-Stahl) creates a groundbreaking VR simulation:

a fully immersive 1937 Chicago, populated by unwitting digital inhabitants.

After Fuller’s mysterious murder, his protégé Douglas Hall (Bierko)

inherits the project and grapples with blackouts and fragmented memories.

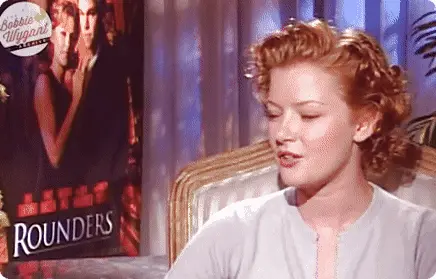

Enter Jane Fuller (Mol), the mogul’s estranged daughter,

who may hold the key to the killing—and to Hall’s own existence.

As Hall delves deeper into the simulation, he uncovers nested realities:

the 1937 world bleeds into 1999, and hints emerge of an even higher layer.

Dennis Haysbert’s detective McBain and Steven Soderbergh’s shadowy presence add layers of paranoia,

echoing The Matrix’s awakening but with a more intimate, noir-infused dread.

What elevates The 13th Floor is its exploration of simulation theory, a la Philip K. Dick,

where inhabitants of lower levels rebel against their programmers, blurring creator and creation.

The film’s effects—pioneering for its time, with seamless transitions

between eras—create a vertigo of realities, far more grounded than The Matrix’s bullet-time bombast.

Goyer’s screenplay, known for Batman Begins, weaves ethical dilemmas: Are simulated lives expendable?

Bierko’s Hall evolves from disoriented everyman to reluctant god, his arc mirroring Deckard’s identity crisis but with sharper existential stakes.

Mol’s Jane, both seductive and spectral, embodies the allure of simulated love,

her chemistry with Bierko fueling the film’s emotional core.

Cinematographer Dietrich Lohmann’s moody palettes—sepia-toned 1930s grit shifting to sterile

1990s fluorescents—heighten the disorientation, while George S. Clinton’s pulsing score underscores the unraveling.

Rusnak, a German filmmaker making his English-language debut, avoids Malick’s poetic indulgence

in The Thin Red Line, opting for propulsive mystery that builds to a mind-bending climax.

The ending, a masterstroke of ambiguity, is the film’s true hook:

Hall and Jane ascend to what seems the “top” level—a sunlit 2024 world free of simulations.

But a final glitch, a flickering doubt, whispers: Are we at the last layer, or just another program?

Unlike The Matrix’s triumphant unplugging, this unresolved tension lingers, inviting rewatches to parse the clues.

The 13th Floor remains a bijou méconnu, overlooked

amid 1999’s Sci-Fi boom, yet it outshines many with its quiet profundity.

< B > My Personal Blog < B > List of all my Blog posts < B >

(c)FPe COPYRIGHT @FPDIEULOIS 2025