by FPDieulois :: 2025-10-25

Beneath the relentless churn of ocean currents lies a renewable powerhouse waiting to be tapped:

tidal energy, harnessed by hydroliennes

sleek underwater turbines that convert the predictable ebb and flow of tides into clean electricity.

Unlike wind turbines that sway with fickle gusts, tidal devices thrive on the moon's gravitational pull,

delivering consistent power around 10,000 times more reliable than solar or wind.

Global potential? Up to 1,200 terawatt-hours annually, enough to power Japan or meet a quarter of Europe's needs.

Yet challenges abound: corrosive saltwater, biofouling from marine life, and installation costs that can top $10 million per megawatt.

Enter the innovators—companies like France's Sabella, Ireland's late OpenHydro, and the shelved Oceade project from Alstom-turned-General Electric

who've propelled this nascent industry from prototypes to grid-connected pilots.

As tidal tech matures, others like Orbital Marine Power and Simec Atlantis Energy

are scaling up, proving hydroliennes could electrify coastlines without a whisper of carbon.

At the forefront stands Sabella, a Breton firm born in 2008 from the tidal streams of the Raz Blanchard, one of Europe's strongest marine currents.

Their D10 turbine, a 10-meter-diameter beast generating 1 megawatt, mimics a windmill submerged on the seabed,

its three blades spinning at 12 revolutions per minute to slice through flows up to 4 meters per second.

Deployed in 2015 off Ushant Island, it clocked over 50 gigawatt-hours before retrieval in 2018,

feeding power to France's grid and lighting up 1,000 homes. Sabella's edge?

A patented yaw system that pivots the turbine to face currents, boosting efficiency to 40% while minimizing mooring stress.

Fast-forward to 2021: Sabella scooped up General Electric's tidal portfolio, inheriting designs from Tidal Generation Limited (TGL), Rolls-Royce, and Alstom

including the Oceade trademark.

This windfall supercharged their D11, a 1.4-megawatt evolution with modular blades for easier maintenance, now eyeing arrays in Brittany and beyond.

"Tidal energy isn't just predictable; it's bankable," says Sabella's CEO Yannick Kerneur, underscoring deployments that have withstood Atlantic storms,

generating revenue through France's feed-in tariffs.

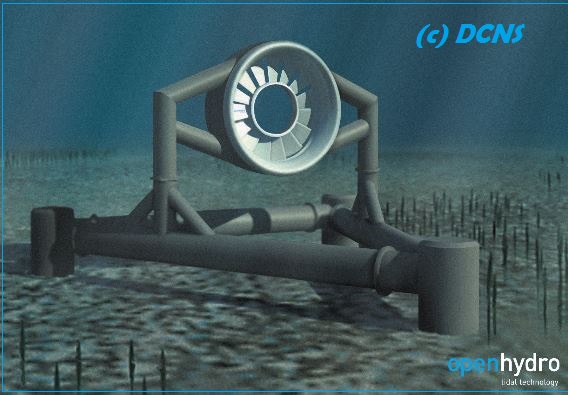

Across the Irish Sea, OpenHydro once embodied tidal ambition with its ducted, open-center turbines

rim-driven rotors encased in a shroud that funnels water like a jet engine, claiming 50% more energy capture than open rotors.

Founded in 2005, the Dublin outfit hit milestones fast: a 250-kilowatt prototype grid-tied at Scotland's European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) in 2008,

followed by a 1-megawatt unit in Canada's Bay of Fundy in 2009. But hubris met headwinds.

In 2013, Naval Group (then DCNS) acquired them for €18 million, deploying two 2-megawatt models at France's Paimpol-Bréhat site in 2016.

Yet grid delays and mechanical gremlins—blade damage in Fundy, unconnected French units—piled up.

By 2018, OpenHydro collapsed into administration, leaving a turbine abandoned on the Fundy seabed,

later slated for removal by newcomer BigMoon.

Their legacy? Over 5,000 operational hours at EMEC, proving seabed gravity-base installs viable,

though at the cost of a cautionary tale on scaling without robust supply chains.

No saga captures tidal's fits and starts like the Oceade odyssey, Alstom's bold 1.4-megawatt pitch that became GE's ghost.

Born from TGL's SeaGen—the world's first megawatt-scale tidal array in Northern Ireland's Strangford Lough,

operational from 2008 to 2016 and churning 11.6 gigawatt-hours

Oceade promised next-gen scalability.

Alstom snapped TGL in 2012, then GE swallowed Alstom's power arm in 2015 for $10.1 billion, rebranding the turbine for harsh currents like Normandy's Alderney Race.

With a 16-meter rotor and direct-drive generator, it aimed for 40% capacity factors, deployable in farms of 50 units.

Pilots loomed: a 2016 demo off Brittany, backed by EDF.

But economics soured. By 2017, GE halted development, citing uncompetitive levelized costs( $200-300 per megawatt-hour versus wind's $50-100)

& redeployed 40 engineers to offshore wind.

The Oceade blueprint, gathering dust until Sabella's 2021 acquisition, highlights tidal's Achilles' heel: upfront costs ballooned

by subsea cabling and decommissioning, deterring investors amid cheaper solar floods.

Yet the field surges with fresh players, undeterred by Oceade's fate. Scotland's Orbital Marine Power

reimagines hydroliennes as surface-piercing floats, their O2 turbine(a 2-megawatt, 72-meter-span rig)

tethered like a buoyant kite off Orkney since 2021, exporting 6 gigawatt-hours yearly to 2,000 homes.

Simec Atlantis Energy, inheritor of Atlantis Resources, powers MeyGen, the globe's largest tidal array in Scotland's Pentland Firth,

with 6.5 megawatts operational and 398 more planned by 2025.

Verdant Power's Kinectic Hydropower system graces New York's East River,

five 30-kilowatt units powering Roosevelt Island since 2019 under a decade-long U.S. license.

France's HydroQuest deploys vertical-axis turbines resilient to debris, testing 1-megawatt models in the Seine estuary.

Andritz Hydro Hammerfest's HS1000, a 1-megawatt horizontal-axis stalwart, logged 20,000 hours in Wales' Anglesey before upgrades.

Emerging: Bluenergy Solutions' modular hydrokinetics for remote rivers, MAKO Turbines' low-cost barrels for global currents,

and Nautricity's CoAXial rotors mimicking fish schools for minimal wake.

These hydroliennes herald a blue revolution, their silent spin weaving tidal might into grids from Fundy to the Solent.

Sabella's resurgence, OpenHydro's hard lessons & Oceade's pivot to Sabella's fold underscore resilience amid volatility.

With costs plummeting 60% since 2010 and pilots proving bankability, tidal could claim 10% of coastal renewables by 2030.

As Orbital's CEO calls it, "The tide waits for no one—nor subsidies."

In an era of net-zero urgency, these underwater sentinels promise power as eternal as the moon itself.

< B > My Personal Blog < B > List of all my Blog posts < B >

(c)FPe COPYRIGHT @FPDIEULOIS 2025